Starting fresh in a new nation

Guest speaker recalls walking thousands of miles as a part of ‘Lost Boys of Sudan.’

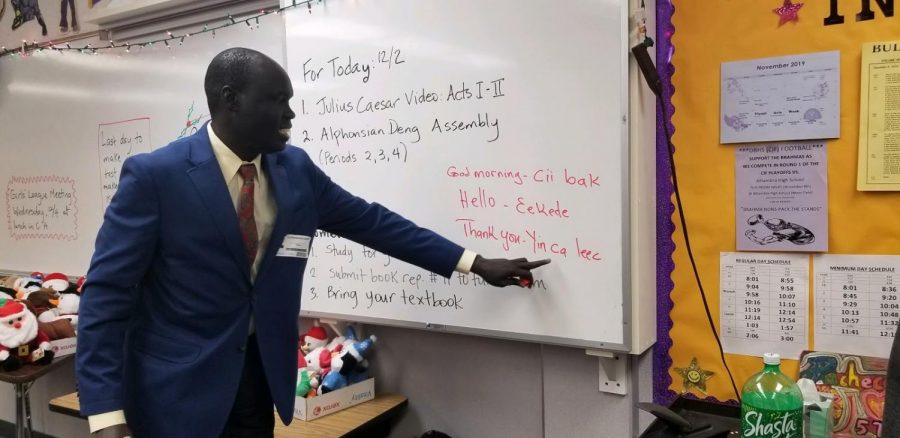

Photo courtesy of Lisa Pacheco

Author Alephonsion Deng, who shared his experience as a Lost Boy of Sudan with students on Dec. 2, shows how to say “Thank you” in his native language.

As government troops descended upon a village in Southern Sudan during the second Sudanese Civil War, about 100,000 boys who would become known as the Lost Boys of Sudan bolted from their homes into unknown territories. One of them was Alephonsion Deng, who spoke in Diamond Bar High School’s theater on Dec. 2 from second period to fourth period.

Deng was seven years old when he was forced to flee his village. According to his manager, Judy A. Bernstein, 16,000 of the Lost Boys survived and made it to the Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya, with 3,600 of them immigrating to the U.S. in 2001.

One story Deng told during his presentation was how he started reading and writing. While attending a school in Kenya, he overheard an elderly man talking about a magic power that nations could use to protect themselves. Deng later asked his teacher about it, and the teacher taught the class how to write the alphabet.

“My message to you really is that education has given me the voice I have today,” he said. “When you want to get the magic power, it’s not gonna be easy, but it’ll change your circumstances.”

Deng also shared the time someone called him “hot” after coming to America. When he was 19 years old and working in Ralph’s, a young woman he said he found attractive greeted him at the checkstand and they began talking. When she was about to leave, she asked if he knew he was “hot.”

Deng didn’t know what that meant at first, so after asking a co-worker if he was “hot,” he ran to the bathroom and began to wash himself. He told his brother what had happened, and his brother told him not to worry.

Deng then told Bernstein what had happened, and she began laughing, but Deng didn’t think it was funny. She told him what “hot” really meant.

“I start thinking about that girl, and I said ‘I missed out,’” he said.

After Deng’s speech, 10 AP English students attended a luncheon where they could ask questions about his experience in America. Deng said that his favorite part about America is that you can develop yourself and reinvent yourself without limitations.

English teacher and Girls’ League adviser Lisa Pacheco met Bernstein through David Putnam, the former detective-turned-novelist who spoke at DBHS in February. Pacheco suggested the idea of Deng speaking at DBHS to instructional dean Julie Galindo, who said hearing his story would help bring it alive for some readers.

“I hope that students and teachers gained a sense of empathy for refugees of war-torn countries, and I also hope that they adopt a welcoming attitude towards these individuals when they enter our country,” Pacheco said via email.

Published in 2005, Deng’s first book, “They Poured Fire On Us From The Sky: The Lost Boys of Sudan,” was co-written by Deng, Bernstein, his brother Benson Deng and his cousin Benjamin Ajak. The memoir focuses on the three Lost Boys’ experiences from the war to moving to America and adapting to American lifestyles and cultures.

His second memoir, “Disturbed In Their Nests,” was published in November 2018 and co-written with Bernstein again. It chronicles the first year of their friendship and their own personal struggles: Deng with living in a new nation and Bernstein with why she wanted to help the Lost Boys and how much she should help them.

After the event, students could purchase the books for $20 each. All of the proceeds will support Deng’s little brother, who will graduate this month from Egerton University in Nairobi, Kenya.

Senior Michelle Aguerrebere attended the event and the luncheon.

“I thought [his presentation] was very inspirational and eye-opening because we take things for granted,” she said. “Our problems are not as big as his.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Diamond Bar High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.