Celebrating different winter holidays

While many start adorning their house with festive lights to brighten the Christmas spirit in December, there are other cultures that prepare for celebrations soon after Thanksgiving.

Hannukah

Also known as the Festival of Lights, Hanukkah, which has roots originating in 160 BC, will take place Dec. 10-18 this year. The days of this celebration vary each year as they go by the ancient Hebrew calendar, which follows the lunar cycle. Hanukkah recognizes the rededication of the Second Temple in Jerusalem after Judaism was outlawed by King Antiochus IV, who forced the Jews to worship Greek gods.

Hanukkah is celebrated by Jewish families by lighting Hanukkah candles. There are eight in total to represent how the oil burns all candles consecutively for eight days. The candles are lit from right to left using an additional candle called the shamash.

Families also play with the dreidel, a four-sided spinning top with Hebrew letters Hay, Gimel, Nun and Shin on each surface. The letters form an acronym for the Hebrew proverb “Nes Gadol Hayah Sham” which pays homage to the religion’s re-dedication. People also eat sufganiyot (fried dough) and latkes (potato pancakes).

Kwanzaa

Introduced by Dr. Maulana Karenga in 1966, Kwanzaa is an African-American holiday taking place from Dec. 26 to Jan. 1. The word ‘Kwanzaa’ is a Swahili term meaning “first” and it celebrates the first harvest by incorporating traditional customs from African countries such as Kenya, Tanzania, Zimbabwe and Uganda. The five values celebrated during the week are ingathering, reverence, commemoration, recommitment and celebration.

Similar to Hanukkah, Kwanzaa uses seven candles–three red, one black and three green–to represent the seven principles of the festivals: umoja (unity), kujichagulia (self-determination), ujima (collective work and responsibility), ujamaa (cooperative economics), nia (purpose), kuumba (creativity) and imani (faith). The colors represent the flags of the African liberation movement. On Dec. 31, presents are exchanged and people celebrate by hosting a mazoa feast of fruit, squash, sweet potatoes and yams.

Omisoka

While Americans are having an annual Times Square ball drop event to mark the new year, the Japanese are traveling to shrines or temples to celebrate Ōmisoka on New Year’s Eve. Japan considers this holiday to be the final day to complete any unfinished businesses in order to prevent misdeeds from carrying over to the next year.

To secure good fortune for the coming year, the Japanese decorate their homes with shimekazari (decorative rope), Kagami mochi (rounded rice cakes) stacked on top of each other and kadomatsu (gateway pine). As traditions prevent individuals from working in kitchens for the first three days of Oshōgatsu (New Years), many households rush to stores for last-minute groceries to finish osechi ryōri, a Japanese traditional meal in bento boxes consisting of herring roe (Kazunoko) and umami wraps (Kombumaki).

In addition, homes are cleaned of any debris and dust to remove any of the past year’s reminisces. As soon as year-end cleaning is over, families gather around to eat a bowl of toshikoshi- udon, or toshikoshi-soba. This is a tradition that originated from the Edo period, and people believe that the noodles breaking off easily with each bite symbolizes the “break” from any hardships from the previous year.

Additionally, the length of the noodles symbolizes health and long life. Lastly, the Japanese will head over to shrines such as Tokyo’s Meiki Shrine to listen to joya no kane, which is the ringing of a temple bell 108 times to represent the cleansing of every earthly sin.

Yalda

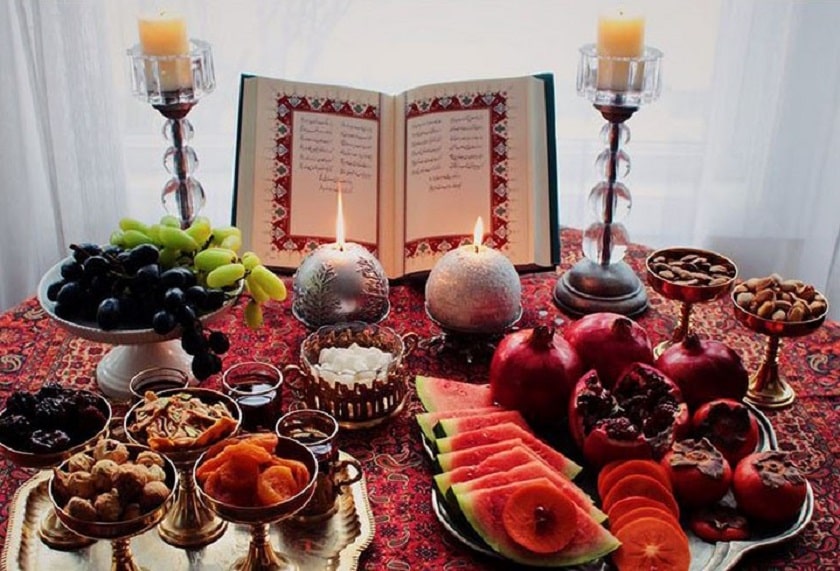

Yalda Night is an Iranian festival recognizing the winter solstice. Additionally to being celebrated in Iran, the holiday is recognized in Central Asian countries such as Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Azerbaijan and Armenia. It comes from “Shab-e Yalda which is Persian for ‘Night of Birth’ and honors the birth of Mitra, the goddess of light. Originating from Zorastrian traditions, the winter solstice was initially seen as a day of mischief, and Yalda Night was a day to protect people from evil during the darkest night. During this time, Iranians also celebrate the transition from autumn to winter.

At night, people stay up late to avoid any horrible deeds, and families gather to share the last harvest of the summer by eating watermelons, nuts and pomegranates. In Iranian culture, watermelons symbolize the sun with its oval shape and it is believed that eating one can protect them from diseases contracted in the winter season.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Diamond Bar High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.