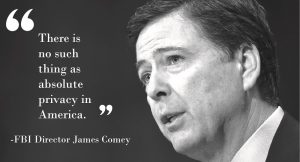

Privacy does not exist

March 21, 2017

The WikiLeaks release of several documents detailing CIA hacking has put the media and public into paranoia once again about the end of what is perceived as individual privacy.

How funny.

Given the pervasiveness of hacking in today’s technological age, the real surprise is the overblown reaction of the public itself. Every system can be hacked into–including classified government files. Think Snowden, who ironically revealed the NSA’s hacking capabilities by leaking private information himself. The fact that the media portrays the situation as some kind of end-of-privacy apocalypse reveals purported exaggeration if not ignorance.

As Nicholas Weaver, senior researcher with the International Computer Science Institute at UC Berkeley succinctly puts it, “That the CIA hacks is like saying water is wet — it’s them doing their job.” Blocking off the CIA from potentially valuable information in an investigation is placing unnecessary obstacles.

Indeed, it is an unsettling thought that your SmartTV might very well be a tool used by the CIA eavesdrop on you.

It is a thought, however, that is unsubstantiated and relies too heavily on pathos.

The CIA has the right to hack into certain devices under specific circumstances, contrary to popular belief. The Fourth Amendment, as proponents cite, grant the right to privacy–against unreasonable searches. This implies that the CIA may hack into personal data given a worthy cause that is authorized by the government in a criminal investigation. It is the same as searching a house with a warrant.

The idea of surveillance isn’t new, either. Prior to the explosion of the digital age, suspected criminals were literally stalked or had their trash dug out for evidence. The privacy of the public is not compromised; only suspected criminals will, and should, be monitored.

Admittedly, the definition of these “suspected criminals” has become ambiguous due to the nature of CIA investigations, which are cloaked in secrecy. The only authority that grants warrants to the CIA is the Fisa court, which has granted 33,942 warrants over a 33-year period with only 12 denials according to the Wall Street Journal. That is suspicious. The numbers suggest that the warrants given are not regulated very closely or strictly by the court. A solution to this problem is for the court, which secretly decides surveillance laws, to have some transparency as to what types of warrants they are granting.

In the end, however, the only people who should be concerned about the CIA’s hacking are those who have committed some crime atrocious enough to put them in the CIA watch list.

They are, after all, the ones affected–not the public. The debate ultimately shouldn’t even be about whether civilians should give up their privacy for the sake of national security, for there is no privacy to be given, but about whether the CIA should be allowed more regulated warrants for surveillance electronically, to which the obvious answer is: yes.